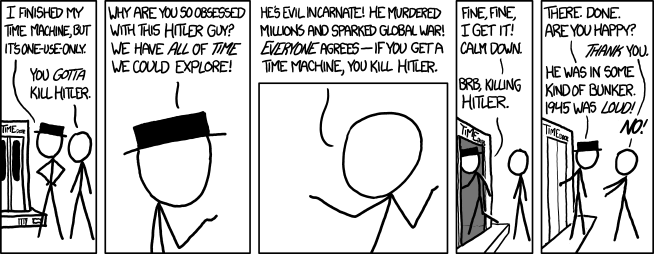

Why There Are No Time Travellers: They Always Do This

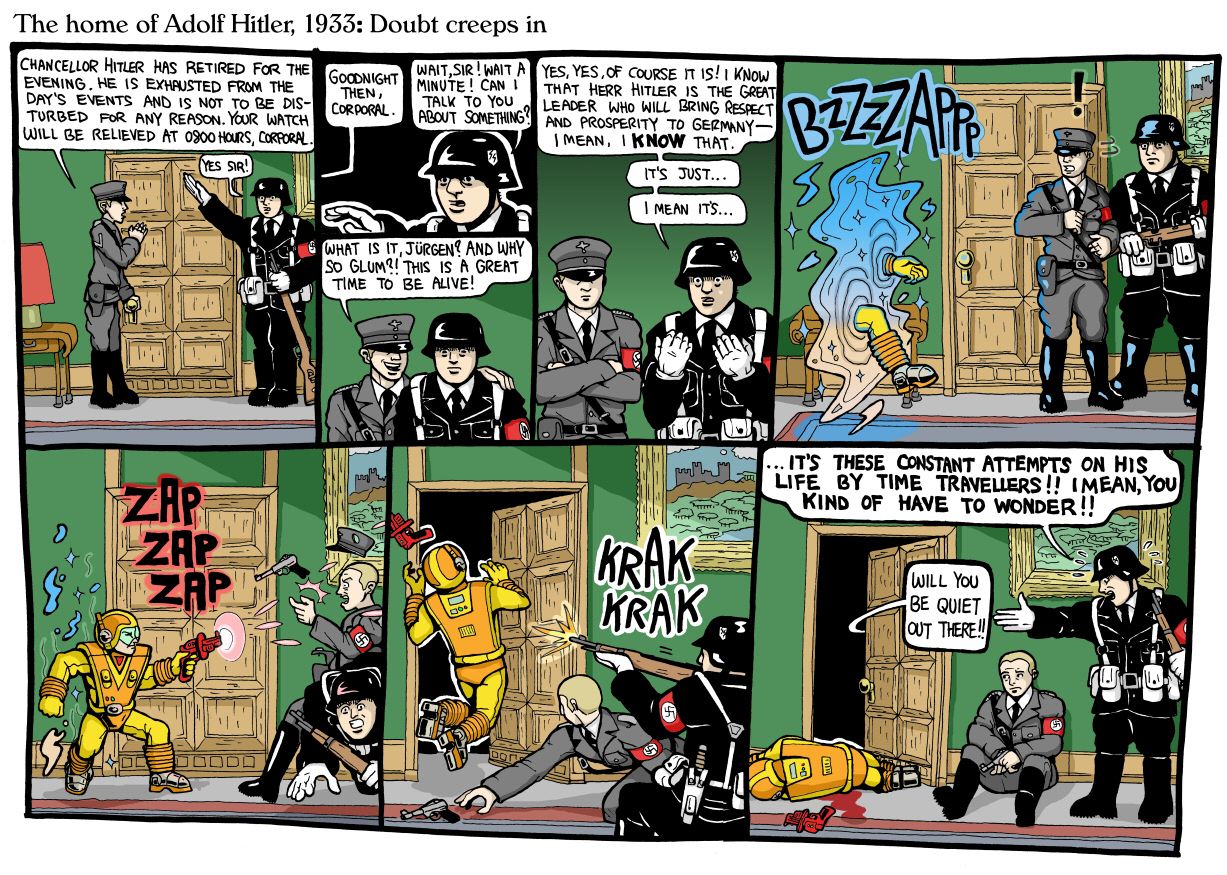

They Always Go For Hitler

International Association of Time Travelers: Members' Forum

Subforum: Europe - Twentieth Century - Second World War

Page 263

11/15/2104

At 14:52:28, FreedomFighter69 wrote:

Reporting my first temporal excursion since joining IATT: have just returned from 1936 Berlin, having taken the place of one

of Leni Riefenstahl's cameramen and assassinated Adolf Hitler during the opening of the Olympic Games. Let a free world

rejoice!

At 14:57:44, SilverFox316 wrote:

Back from 1936 Berlin; incapacitated FreedomFighter69 before he could pull his little stunt. Freedomfighter69, as you are

a new member, please read IATT Bulletin 1147 regarding the killing of Hitler before your next excursion. Failure to do so

may result in your expulsion per Bylaw 223.

At 18:06:59, BigChill wrote:

Take it easy on the kid, SilverFox316; everybody kills Hitler on their first trip. I did. It always gets fixed within

a few minutes, what's the harm?

At 18:33:10, SilverFox316 wrote:

Easy for you to say, BigChill, since to my recollection you've never volunteered to go back and fix it. You think

I've got nothing better to do?

11/16/2104

At 10:15:44, JudgeDoom wrote:

Good news! I just left a French battlefield in October 1916, where I shot dead a young Bavarian Army messenger named

Adolf Hitler! Not bad for my first time, no? Sic semper tyrannis!

At 10:22:53, SilverFox316 wrote:

Back from 1916 France I come, having at the last possible second prevented Hitler's early demise at the hands of

JudgeDoom and, incredibly, restrained myself from shooting JudgeDoom and sparing us all years of correcting his

misguided antics. READ BULLETIN 1147, PEOPLE!

At 15:41:18, BarracksRoomLawyer wrote:

Point of order: issues related to Hitler's service in the Bavarian Army ought to go in the World War I forum.

11/21/2104

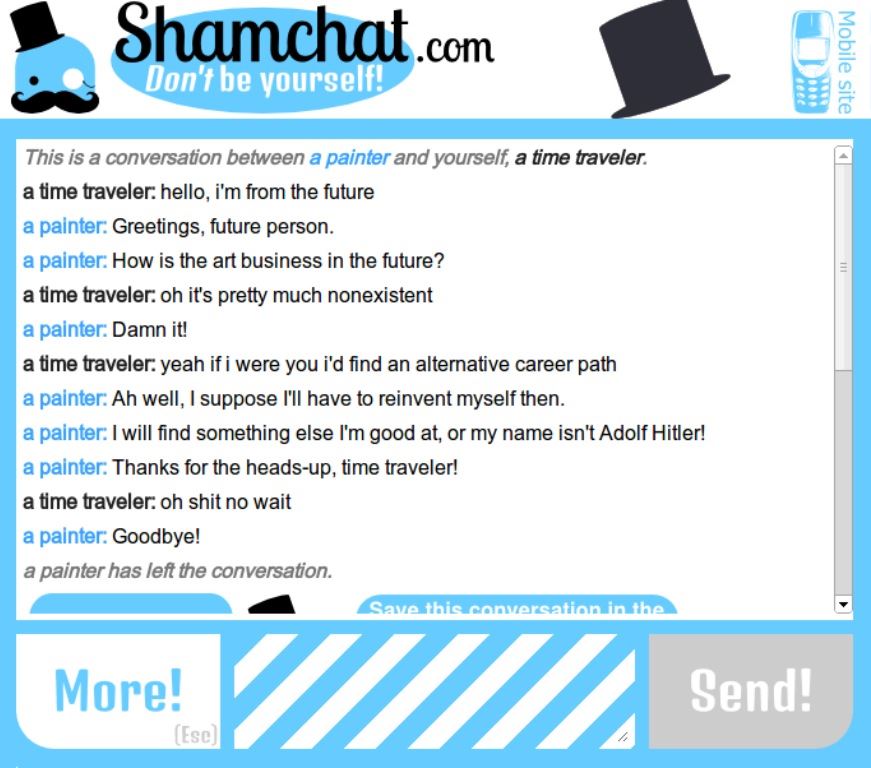

At 02:21:30, SneakyPete wrote:

Vienna, 1907: after numerous attempts, have infiltrated the Academy of Fine Arts and facilitated Adolf Hitler's

admission to that institution. Goodbye, Hitler the dictator; hello, Hitler the modestly successful landscape artist!

Brought back a few of his paintings as well, any buyers?

At 02:29:17, SilverFox316 wrote:

All right; that's it. Having just returned from 1907 Vienna where I secured the expulsion of Hitler from the Academy

by means of an elaborate prank involving the Prefect, a goat, and a substantial quantity of olive oil, I now turn

my attention to our newer brethren, who, despite rules to the contrary, seem to have no intention of reading

Bulletin 1147 (nor its Addendum, Alternate Means of Subverting the Hitlerian Destiny, and here I'm looking at you,

SneakyPete). Permit me to sum it up and save you the trouble: no Hitler means no Third Reich, no World War II,

no rocketry programs, no electronics, no computers, no time travel. Get the picture?

At 02:29:49, SilverFox316 wrote:

PS to SneakyPete: your Hitler paintings aren't worth anything, schmuck, since you probably brought them

directly here from 1907, which means the paint's still fresh. Freaking n00b.

At 07:55:03, BarracksRoomLawyer wrote:

Amen, SilverFox316. Although, point of order, issues relating to early 1900s Vienna should really go in

that forum, not here. This has been a recurring problem on this forum.

11/26/2104

At 18:26:18, Jason440953 wrote:

SilverFox316, you seem to know a lot about the rules; what are your thoughts on traveling to, say,

Braunau, Austria, in 1875 and killing Alois Hitler before he has a chance to father Adolf? Mind you,

I'm asking out of curiosity alone, since I already went and did it.

At 18:42:55, SilverFox316 wrote:

Jason440953, see Bylaw 7, which states that all IATT rulings regarding historical persons apply to

ancestors as well. I post this for the benefit of others, as I already made this clear to young Jason

in person as I was dragging him back from 1875 by his hair. Got that? No ancestors. (Though if anyone

were to go back to, say, Moline, Illinois, in, say, 2080 or so, and intercede to prevent Jason440953's

conception, I could be persuaded to look the other way.)

At 21:19:17, BarracksRoomLawyer wrote:

Point of order: discussions of nineteenth-century Austria and twenty-first-century Illinois should be

confined to their respective forums.

12/01/2104

At 15:56:41, AsianAvenger wrote:

FreedomFighter69, JudgeDoom, SneakyPete, Jason440953, you're nothing but a pack of racists. Let the

light of righteousness shine upon your squalid little viper's nest!

At 16:40:17, BigTom44 wrote:

Well, here we frickin' go.

At 16:58:42, FreedomFighter69 wrote:

Racist? For killing Hitler? WTF?

At 17:12:52, SaucyAussie wrote:

AsianAvenger, you're not rehashing that whole Nagasaki issue again, are you? We just got everyone

calmed down from last time.

At 17:22:37, LadyJustice wrote:

I'm with SaucyAussie. AsianAvenger, you're making even less sense than usual. What gives?

At 18:56:09, AsianAvenger wrote:

What gives is everyone's repeated insistence on a course of action which, even if successful,

would only save a few million Europeans. It would be no more trouble to travel to Fuyuanshui,

China, in 1814 and kill Hong Xiuquan, thus preventing the Taiping Rebellion of the mid-nineteenth

century and saving fifty million lives in the process. But, hey, what are fifty million yellow devils

more or less, right, guys? We've got Poles and Frenchmen to worry about.

At 19:01:38, LadyJustice wrote:

Well, what's stopping you from killing him, AsianAvenger?

At 19:11:43, AsianAvenger wrote:

Only to have SilverFox316 undo my work? What's the point?

At 19:59:23, SilverFox316 wrote:

Actually, it seems like a pretty good idea to me, AsianAvenger. No complications that I can see.

At 20:07:25, Big Chill wrote:

Go for it, man.

At 20:11:31, AsianAvenger wrote:

Very well. I shall return in mere moments, the savior of millions!

At 20:14:17, LadyJustice wrote:

Just checked the timeline; congrats on your success, AsianAvenger!

12/02/2104

At 10:52:53, LadyJustice wrote:

AsianAvenger?

At 11:41:40, SilverFox316 wrote:

AsianAvenger, we need your report, buddy.

At 17:15:32, SilverFox316 wrote:

Okay, apparently AsianAvenger was descended from Hong Xiuquan. Any volunteers to go back and

stop him from negating his own existence?

12/10/2104

At 09:14:44, SilverFox316 wrote:

Anyone?

At 09:47:13, BarracksRoomLawyer wrote:

Point of order: this discussion belongs in the Qing Dynasty forum. We're adults; can we keep sight

of what's important around here?

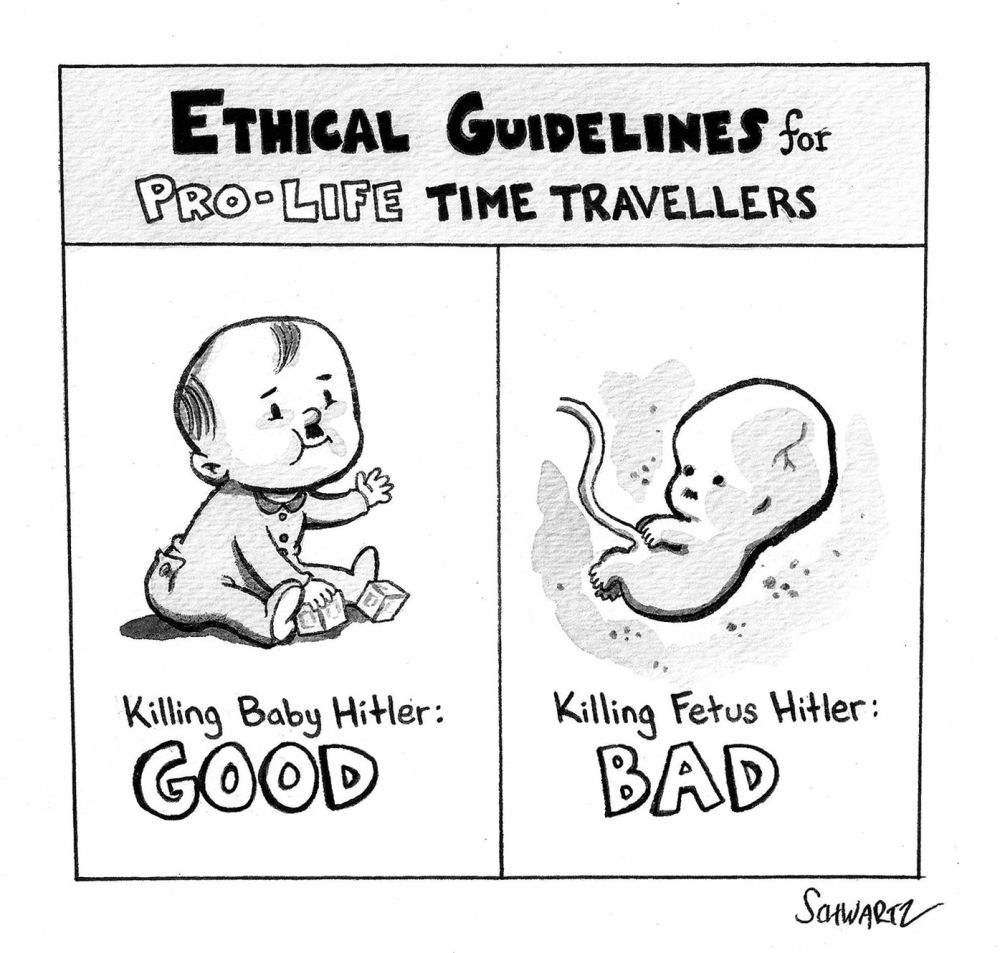

But, of course, those assumptions are strong. Too strong. Here are just a few of the issues you'd need to sort out before even starting to intelligently consider whether killing baby Hitler would be wise.

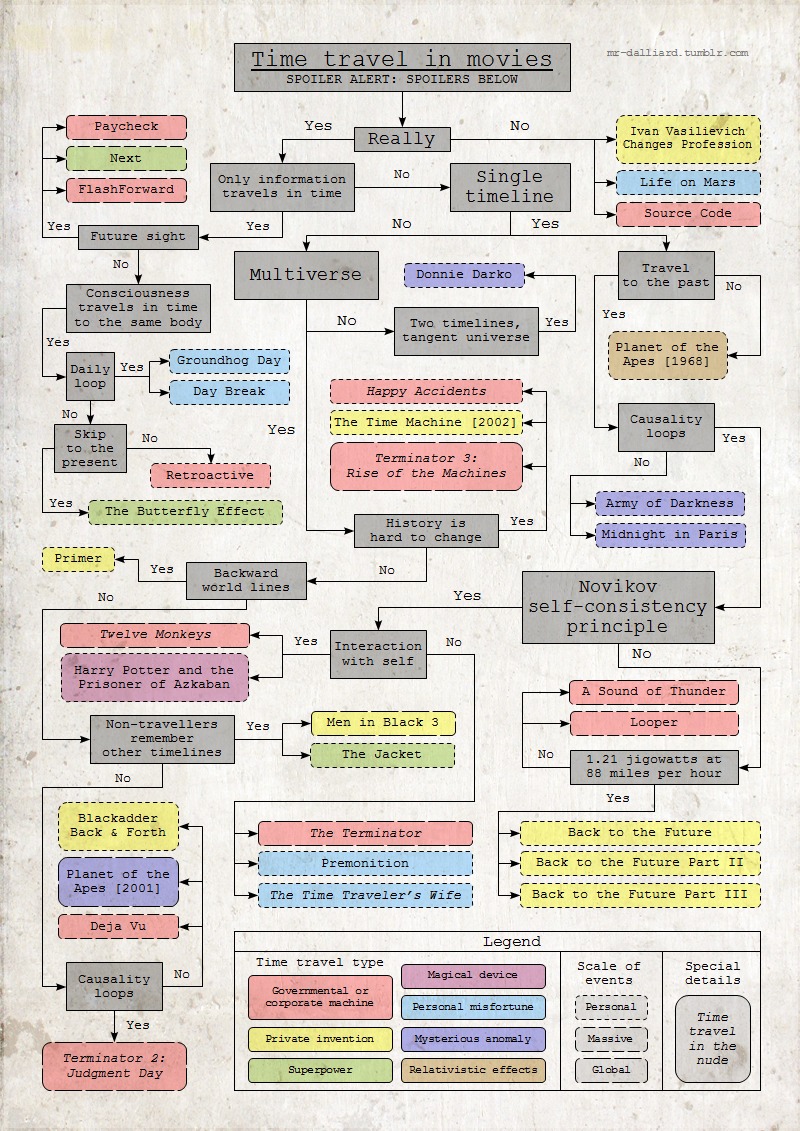

Can time travel actually change history?

The first question here is whether backward time travel is actually functionally possible. This is a different question from whether it's technically possible. It seems quite plausible that backward time travel could exist but that it would be impossible to actually change the course of history using it. This is how time travel is depicted in movies like 12 Monkeys or The Terminator, where, in my colleague Matt Yglesias's words, "temporal jumping simply turns out to be a feature of a universe that is nonetheless an unchanging four-dimensional block." In Terminator, for example, Kyle Reese is sent back to protect Sarah Connor, because her son John will later become an anti-Skynet resistance leader. But Reese winds up fathering John. His time travel was a part of the timeline all along.

This idea — that time travel could be possible but must be consistent with the past as it has already taken place — is known among physicists as the Novikov self-consistency principle. It's possible that this principle is wrong, but it behooves people who think past-altering time travel is possible to explain how to avoid paradoxes. Take, for instance, the most famous time travel problem, the grandfather paradox: Suppose you go back in time and kill your grandfather before your mother/father has been conceived. This action creates a world in which you exist but your existence is logically impossible. Things like that just can't happen, which is why many physicists and philosophers embrace the Novikov self-consistency principle. The late, great philosopher David Kellogg Lewis explained this well in his 1976 paper "The Paradoxes of Time Travel":

If Tim did not kill Grandfather in the "original" 1921, then if he does kill Grandfather in the "new" 1921, he must both kill and not kill Grandfather in 1921—in the one and only 1921, which is both the "new" and the "original" 1921. It is logically impossible that Tim should change the past by killing Grandfather in 1921. So Tim cannot kill Grandfather.

There are some fictional depictions of attempted retroactive Hitler assassinations that explain how this principle works in practice. In "Cradle of Darkness," an episode of the 2002-'03 reboot of the Twilight Zone, Katherine Heigl's character is sent back in time to kill baby Hitler. She succeeds — but Hitler's mother adopts another baby and raises it as Adolf, who grows up to lead the Nazi Party, start World War II, carry out the Holocaust, etc.

Somewhat similarly, Eric Norden's 1977 novella The Primal Solution imagines an elderly Jewish scientist and Holocaust survivor attempting to go back in time, control Hitler's mind, and force him to drown himself. Hitler survives, identifies the force trying to kill him as Jewish, and becomes a vociferous anti-Semite, setting the Nazi rise to power and the Holocaust into motion.

These aren't very satisfying versions of Hitler-killing time travel. But they're versions that obey the Novikov self-consistency principle, and thus make considerably more internal sense than versions in which you really can go back in time and kill the actual Hitler.

Can we have any sense of what the ramifications of killing Hitler would be?

Okay, so time traveling metaphysics are tricky. Let's get ourselves out of this thicket, then, by supposing instead that no time traveling takes place and instead we're an Austrian living in the town of Braunau am Inn in 1889 who has a strong premonition that the wee baby Adolf is going to grow up to kill tens of millions of people, and we are thus driven to kill him. You know your predictions are correct. No time travel paradoxes are going to be created. Do you do it?

Well … maybe? It depends on quite a few factors. For one thing, baked into the premise of this question is the idea that the Nazis would not have risen to power, launched World War II, and carried out the Holocaust were it not for the existence of Adolf Hitler. You could certainly imagine a history in which Hitler didn't exist, the party lacked a charismatic leader, and it never came to power. Germany muddled through the Great Depression, the Weimar Republic kept going, and World War II never arose.

But you can also imagine a history in which another leader emerged who was even more effective than Hitler. This is the story offered by the comedian Stephen Fry in his novel Making History. In it, a history graduate student named Michael Young goes back in time and renders Hitler's father infertile. However, the Nazi Party still takes power, under a leader named Rudolf Gloder who, lacking Hitler's personal character flaws, is able to acquire nuclear weapons, obliterate Moscow and St. Petersburg, conquer almost all of Europe permanently, exterminate the continent's Jewish population, and carry on a cold war with the US indefinitely.

You could also imagine an alternate history where the Nazis don't take power but the Völkisch movement in post-WWI Germany gives rise to another virulently anti-Semitic regime, or at least a regime that also sparks a second world war. Or maybe Germany is fine, but absent WWII, tensions between the US and the Soviet boil into a hot war that is even bloodier and more destructive than the actual Second World War was. Maybe this war doesn't lead to the kind of postwar human rights revolution that WWII actually did, slowing the spread of liberal democracy and causing additional suffering for millions.

All of which is to say: We have no idea how the world would have differed if Hitler had died in infancy. We don't know how much weaker, or stronger, the Nazi Party would've been. We don't know if a second UK/France/Russia versus Germany war could've been avoided and, if so, whether another, bloodier war would've occurred instead. And unless we have answers on that, we can't know the consequences of killing Hitler and thus whether killing Hitler did more good than harm.

Bush, to his credit, glancingly admits this uncertainty. "It could have a dangerous effect on everything else," he told the Huffington Post, but then continues: "but I'd do it — I mean, Hitler."

If we can't know if killing Hitler is right or wrong, can we know if anything is right or wrong?

This is actually a general problem for consequentialist moral theories — that is, theories where the morality of an action depends entirely on what the consequences of that action would be. In his classic 2000 paper "Consequentialism and Cluelessness," the University of Sheffield's James Lenman explained the issue using the case of a German bandit in the year 100 BCE attempting to decide whether to kill a distant ancestor of — you guessed it — Adolf Hitler:

Imagine we are in what is now southern Germany a hundred years before the birth of Jesus. A certain bandit, Richard, quite lost to history, has raided a village and killed all its inhabitants bar one.This final survivor, a pregnant woman named Angie, he finds hiding in a house about to be burned. On a whim of compassion, he orders that her life be spared. But perhaps, by consequentialist standards, he should not have done so. For let us suppose Angie was a great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great great grandmother of Adolf Hitler. The millions of Hitler's victims were thus also victims of Richard's sparing of Angie.

Do Hitler's crimes mean that Richard acted wrongly, in consequentialist terms? They do not. For Hitler's crimes may not be the most significant consequence of Richard's action. Perhaps, had Richard killed Angie, her son Peter would have avenged her, thus causing Richard's widowed wife Samantha to get married again to Francis. And perhaps had all this happened Francis and Samantha would have had a descendant 115 generations on, Malcolm the Truly Appalling, who would have conquered the world and in doing so committed crimes vastly more extensive and terrible than those of Hitler.

Lenman's point is that if morality is really about maximizing good consequences, then it's a problem that the immediate consequences of an action like killing an innocent villager can be swamped by the consequences thousands of years in the future, which no one could ever reasonably foresee. Maybe I met someone at a bar last weekend whose progeny 2,000 years from now will cause human extinction. That would imply that the worst thing I ever did in my entire life was refrain from murdering that bar acquaintance. This seems to imply that there's basically no way to know if you're making the right ethical decisions. Either ethical living is impossible, or a moral theory less dependent on actions' consequences is needed.

I'm less pessimistic than Lenman is. As Tyler Cowen argued in a response paper, the existence of serious uncertainty is important, and humbling, but doesn't render estimation of an event's likely effects totally impossible. If we know the near-term effects of foiling a nuclear terrorism plot are that millions of people don't die, and don't know what the long-term effects will be, that's still a good reason to foil the plot.

But the "epistemic critique," as Lenman's argument has come to be known, is important when we're considering less direct consequences, like the effects of murdering an infant in 1889 on war and peace in 1939. This isn't like foiling a nuclear bomb plot. We just don't know what the consequences of killing Hitler would've been at any point. That renders the problem of Hitler infanticide all but unsolvable.

A PSA

Robert Heinlein "All You Zombies."

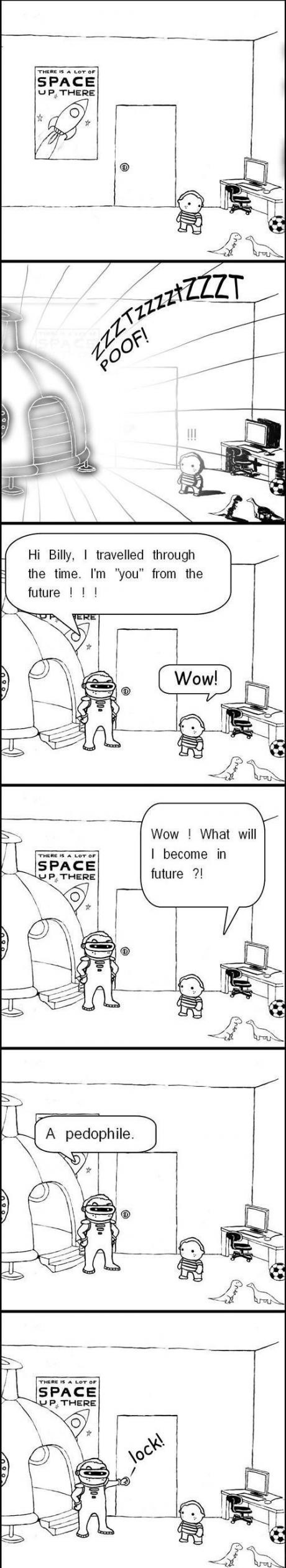

A baby girl is mysteriously dropped off at an orphanage in Cleveland in 1945. "Jane" grows up lonely and dejected, not knowing who her parents are, until one day in 1963 she is strangely attracted to a drifter. She falls in love with him. But just when things are finally looking up for Jane, a series of disasters strike. First, she becomes pregnant by the drifter, who then disappears. Second, during the complicated delivery, doctors find that Jane has both sets of sex organs, and to save her life, they are forced to surgically convert "her" to a "him." Finally, a mysterious stranger kidnaps her baby from the delivery room.

Reeling from these disasters, rejected by society, scorned by fate, "he" becomes a drunkard and drifter. Not only has Jane lost her parents and her lover, but he has lost his only child as well. Years later, in 1970, he stumbles into a lonely bar, called Pop's Place, and spills out his pathetic story to an elderly bartender. The sympathetic bartender offers the drifter the chance to avenge the stranger who left her pregnant and abandoned, on the condition that he join the "time travelers corps." Both of them enter a time machine, and the bartender drops off the drifter in 1963. The drifter is strangely attracted to a young orphan woman, who subsequently becomes pregnant.

The bartender then goes forward 9 months, kidnaps the baby girl from the hospital, and drops off the baby in an orphanage back in 1945. Then the bartender drops off the thoroughly confused drifter in 1985, to enlist in the time travelers corps. The drifter eventually gets his life together, becomes a respected and elderly member of the time travelers corps, and then disguises himself as a bartender and has his most difficult mission: a date with destiny, meeting a certain drifter at Pop's Place in 1970.

The question is: Who is Jane's mother, father, grandfather, grand mother, son, daughter, granddaughter, and grandson? The girl, the drifter, and the bartender, of course, are all the same person. These paradoxes can made your head spin, especially if you try to untangle Jane's twisted parentage. If we draw Jane's family tree, we find that all the branches are curled inward back on themselves, as in a circle. We come to the astonishing conclusion that she is her own mother and father! She is an entire family tree unto herself.

The Shining Girls by Lauren Beukes

A man named Harper Curtis living in depression-era Chicago comes upon a house – or House, as it is capitalised in the novel – that is a portal to other times. Inside there's a dead man on the floor, and on the walls a constellation of unrelated artefacts, among them a pair of butterfly wings, a baseball card and a contraceptive pill. Next to these objects are the names of women, scrawled in Harper's own handwriting. When he looks out of the window the world beyond seems to be in a time-lapse film: "The houses across the way change. The paint strips away, recolours itself, strips away again through snow and sun and trash tangled up with leaves blowing down the street."

We know Harper isn't much troubled by conscience because he throttled a blind woman to get the key to the House in the first place, and once inside he is quickly overcome with the urge to kill the "shining girls" signified by the names and keepsakes. His motives are mysterious. There are hints of the bliss-in-murder mysticism found in Alan Moore's graphic novel From Hell, but for the most part his reasons don't go any further than a penchant for cruelty, worked up by the inexplicable forces of the House.

And so he moves between 1929 and 1993, slaying his predetermined victims as he goes and leaving anachronistic items with the bodies. For an extra kick he enjoys masturbating over the scenes of his crimes, decades before or after he commits them: "He likes the juxtaposition of memory and change. It makes the experience sharper."

Not all his attacks are successful. Kirby, a young woman living in 1989, survives one of his assaults and vows to find her would-be killer. She becomes an intern at the Chicago Sun-Times newspaper to get her hands on evidence of a possible link between her ordeal and a series of other murders, befriending a lovesick old hack to help her with her quest. Meanwhile Harper is looping the loop through time, hoping to bump into Kirby again so he can finish the job.

Beukes has enormous fun with the concept. When Harper travels to 1988 he "stands entranced by the whirling and flaying brush strips of a car wash". He visits the Sears Tower under construction in 1972, and then returns a year later – or a day later, in his time – to take the elevator to the top. "The view makes him feel like a god."

Yet it is 1930s Chicago that is the most pungent and evocative era in the novel. Beukes's writing is at its most surprising here, recalling the cadences of Denis Johnson: when Harper surveys the sorry patients of a run-down hospital, they are described as having "the same look of resignation he's seen in farm horses on their last legs, ribs as pronounced as the cracks and furrows in the dead earth they strain the plow against. You shoot a horse like that."

The Time Traveller by Isaac Asimov

When It Comes to Time Travel, There's No Time Like the Present

By ISAAC ASIMOV

Modern writers who have attempted science fiction or fantasy have, on numerous occasions, ventured on plots in which the hero or heroine has gone back into the past. Mark Twain's ''Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court,'' published in 1889, was the first. Works by such writers as Jack Finney, Ray Bradbury and L. Sprague de Camp followed. Lately, there have been motion pictures on the theme, including ''Back to the Future,'' released in 1985, and ''Peggy Sue Got Married,'' which closes the New York Film Festival tonight and begins its commercial run Wednesday.

Why this interest in going back in time? For one thing, it enables one to have fun with anachronisms, to say nothing of the possibly hilarious confusion of the time traveler who finds himself out of time and of the equal confusion of those who must deal with such a person. More seriously, it enables the writer to lend a sharper point to satire, since the protagonist (and the reader or viewer) knows the future, while all the other characters in the story don't.

Nevertheless, I suspect that the chief point in concocting such a story rests with the fact that human beings have a hankering to return to the past, so that tales dealing with such an event are quite likely to be popular. I'm sure that every one of us has at one time or another felt the urge to step back into the past, even if only briefly. But, before considering why that should be, let me disappoint you.

In many science-fiction stories, the trip into the past is by way of some futuristic machine that can take you through time at will, as an automobile or airplane takes you through space. Such a machine was first used in H. G. Wells's ''Time Machine,'' published in 1895, and one was used in ''Back to the Future.'' That, however, is totally impossible on theoretical grounds. It can't and won't be done.

Nevertheless, even if time travel is not in the cards, does it not remain a beautiful dream?

I must disappoint you again. It's not a beautiful dream, it's a nightmare. Let me explain.

One reason to want to go into the past is to experience youth again. Why not? Youth is better than old age. How wonderful to have young limbs pumping tirelessly again in place of the creaky old body you now have. You may think longingly of the simple joys of youth; the security of being cared for by your parents; the fun of play, and so on, and so on, and so on.

But in order for this to be meaningful, you must go back into the past with your adult memories intact (as was true for both the Con-necticut Yankee and Peggy Sue). If you're a youngster again, but with only the youngster's memory, you simply live your life once again, without any sense of glory in youth and health and fun. If, however, you do have your adult memories, you can appreciate and delight in the change - except that, knowing the future, you know what lies ahead. You know that at such and such a time you will experience a serious accident, or a terrible disease, or have someone you love die. That would make life unbearable, I promise you. It is only because we can't foresee the future that our lives are bearable right now.

Besides that, youth was not the pleasurable time you may think it was. Our memories are treacherous, eliminating the unpleasant and painting the pleasant in unrealistically bright colors. I took the precaution of keeping a diary from the age of 18, so I know this. If you kept a diary, you would, too. Take my advice and be as you are, old and decrepit though you may be. Why subject yourself to disillusion and find that your dearest memories are cobwebs of illusion?

You may decide, of course, that you don't want to go back and relive your youth. You merely want to see your parents again, your little sister, your old cronies, the old swimming hole -whatever.

Thornton Wilder did this magnificently in his drama ''Our Town,'' produced in 1938. The heroine, who had a chance to go back after death, simply broke her heart. She couldn't endure watching everyone live as though life were eternal, and not cherishing each other while they had the chance.

The truth is even less romantic than this. Undoubtedly, you will find that your parents are not quite as you remember them, nor your family, nor your friends, nor your surroundings. Everything will be smaller, dumber, less interesting. Again for your pains, you will have disillusionment. Far from regaining youth for a second time, you will lose what you had (in memory) the first time.

But then, you may not want to go back into the past to relive your own life or to renew your old memories. You might just want to go back to a simpler time - a time before the problems of today, a time before the nuclear threat, terrorism, drugs, traffic tie-ups, pollution and the myriad of ills society seems heir to now. Thus, Jack Finney, in his ''Third Level,'' written in the aftermath of World War II, had his hero go back to the last decades of the 19th century, and leaves him sitting on a porch, sipping cider through a straw in the quiet twilight.

The hero is living a quiet middle-class life. Let him visit the city slums of the 1880's; however, remember that before the Great Depression, the Government of the United States felt no responsibility whatever for the poor. Or let him continue to sip cider until he feels the need for some entertainment, in which case he'd better enjoy a quilting party, for there were neither movies nor television to amuse him. And he'd better not get sick. No antibiotics, no modern surgical techniques. Then, too, he has to live with the sure knowledge that the 20th century is coming with its world wars, Fascism, Communism and everything else. Restful? I think not.

But hold on. Suppose you're not going into the past merely to relive a simpler or more youthful time in a passive manner. Suppose you're going back for some active point. You are going to change your life. You're going to find the fork where you took the wrong turning (haven't we all gone wrong at some time or other?) and change it. (In the drama, ''Morning's at Seven,'' there is one character who constantly leaned against a tree, saying, ''I've got to find the fork.'') Peggy Sue, for instance, finding herself back in the past, is determined not to marry the very unpleasant young man she had married, because the marriage had proved to be an unhappy one.

However, taking the other road when you come to the fork is not merely going to change one consequence and leave everything else unaltered. The other road is going to lead to innumerable unforeseen consequences, while the first road, left untrodden, is going to remove equally innumerable consequences you might not want removed. For instance, to take a very simple example, if you decide to wipe an unsatisfactory husband out of your life, it may be that he provided you with a child you adore. That child gets wiped out with your husband, of course, and you have to weigh the benefits against the harm. In fact, for all you know, taking the other road may lead to an agonizing death for you the next day. How can you dare touch anything?

Ray Bradbury made that point marvelously in his ''Sound of Thunder.'' Hunting safaris go back into the Mesozoic era to track and possibly kill dinosaurs. This is done in strictly restricted areas and under restricted conditions calculated to prevent any change in the future. One person carelessly steps outside the bounds and unintentionally kills a butterfly. The present world is enormously changed, in consequence.

Or, perhaps, the time traveler doesn't want to change his life but merely use his foreknowledge to become wealthy. Thus, Peggy Sue discovers that way back in the dark ages of 1960, there were no pantyhose. There is a scene, then, where Peggy Sue is shown sewing pantyhose perhaps with the intention of making herself rich, rich, rich. This is not followed up but it is not likely that the mere existence of one pantyhose is going to lead to wealth. It may seem, after the fact, that there is an overwhelming demand for pantyhose, but that demand had to be created by publicity and advertising campaigns that would require a great deal more capital than Peggy Sue would be likely to have.

The same probably goes for any other get-rich-quick scheme the time traveler has. He may know the next Derby winner or what the stock market will do, but his first few winnings will undoubtedly change reality in such ways that his foreknowledge is wiped out.

But, then, the time traveler may be a true idealist. He (or she) may not care what happens to himself as a person. He may be intent on changing the world for the better, overall, and damn the particular consequences.

Thus, it was the Connecticut Yankee's dream to introduce 19th-century American initiative and technology into King Arthur's court, thus wiping out slavery and the backward mummery of Merlin (the villain of the story). Again, in L. Sprague de Camps's ''Lest Darkness Fall,'' the hero, Martin Padway, goes back to Ostrogothic Italy just before Belisarius's campaigns to wipe out what is left of Roman civilization in the West and introduce the ''dark age.'' Padway strives manfully to introduce 20th-century technology and prevent the dark age.

Would such grandiose schemes succeed? Personally, I think not. It is very unlikely that one can graft the technology of one century onto the social system of another. In other words, ''you can't have steam engines until it is steam-engine time.''

Besides, what may seem a desirable change to one person may not necessarily seem so to another. There have been a number of stories written of people who go back into the past and seize an opportunity (or plan one from the beginning) to prevent the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. (Naturally, such a scheme of prevention always fails.) On the other hand, some other person finding himself a few years farther in the past may be an ardent Confederate patriot and may exert himself to bring about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln before he took office.

Would the former change have really prevented the ills of the Reconstruction period? Would the latter change have really led to the Union's loss of the Civil War and the establishment of an independent Confederacy? Do we really know? - And what other consequences would follow in either case? Do we really know?

In short, going back into the past is not going to help anyone. Whatever a time traveler's purpose is likely to be, he will surely be disappointed.

We may continue to dream on (there is no charge for dreams) but let us be glad, then, that time travel is impossible.

Finding Time Travellers

There’s a lot we don’t know about time travel. Whether it exists, for example.

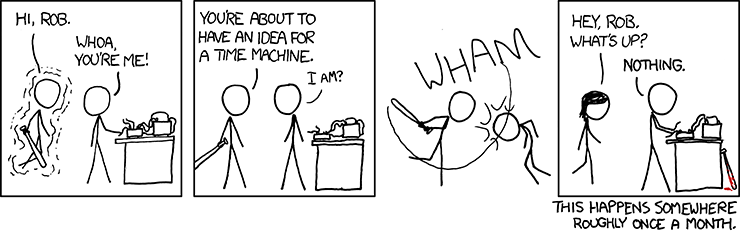

Just for the sake of argument, let’s assume time travel is theoretically possible. Even so, the fact that we aren’t aware of any time travelers isn’t particularly surprising. Making a big change far in the past, one that would conclusively announce to the world that time travel is real, could potentially change history such that the time traveler would never be born in the first place.

But according to a real study conducted by pair of physics professors at Michigan Technical University, there may be a way to locate time travelers - and it involves Twitter.

Released late last month, ‟Searching the Internet for evidence of time travelers” attempts to find real-world Marty McFlys by searching for information online that couldn’t have been posted without foreknowledge of the future.

‟Were a time traveler from the future to access the Internet of the past few years, they might have left once-prescient content that persists today,” the authors speculate. ‟Alternatively, such information might have been placed on Internet by a third party discussing something unusual they have heard. Such content might have been catalogued by search engines such as Google...or Bing...or remain in posts left on Facebook...Google Plus...or Twitter.”

For their analysis, the authors selected a pair of search terms that would have been completely unknown before a specific date in recent history and then looked for Internet traffic relating to those terms before the sets dates. The terms they looked at were ‟Comet ISON”, a comet first discovered on September 21, 2012, and ‟Pope Francis,” the name selected by Jorge Mario Bergoglio on March 16, 2013 when he ascended to the head of the Catholic Church.

The researchers dug through everything from Google data to Twitter hashtags in an attempt to find any mention of Comet ISON or Pope Francis in the time leading up to when those names became widely known.

Many search avenues were stymied by technological limitations. Namely, the ability to backdate Facebook status updates, making them appear as if they were posted earlier than they actually were. Additionally, Google Trends only shows results for search terms that have already received a large amount of interest, which makes it hard to find a time traveler’s single post predicting Pope Francis would be named Esquire’s Best Dressed Man of the Year.

In addition to looking for evidence of time travelers online, the researchers also reached out to any potential time travelers directly by writing a post on an online message board asking people from the future to tweet using one of two pre-specified hashtags before a certain date that had already occurred. The hashtags (#ICanChangeThePast2 and #ICannotChangeThePast2) were aimed at letting time travelers tell the researchers about the nature of time travel and whether actions taken while traveling in the past can change events in the future.

Famed physicist Stephen Hawking attempted something similar in 2012 by throwing a party for time travelers but only sending out invitations after the fact. ‟I sat there a long time,” Hawking told an interviewer, ‟but no one came."

Sadly, the reachers looking for time travelers on the Internet turned up similarly empty-handed on all fronts. No convincing prescient information was located anywhere on the Internet about Pope Francis or Comet ISON, and no one tweeted using the specified hashtags before the request to do so was posted.

‟Although the negative results reported here may indicate that time travelers from the future are not among us and cannot communicate with us over the modern day Internet, they are by no means proof,” the researchers wrote, noting that it’s possible a time traveler’s changing the past in any way could "violate some yet-unknown law of physics.”

Or maybe time travelers just aren’t all that interested in the new pope.

Would You Want a Time Machine?

You want a time machine, don't you?

Because one in 10 Americans do—at least that's what they said when Pew Research Center asked what futuristic technology they would like to own.

That's a notable percentage of people, especially when you consider that survey respondents came up with "time machine," unprompted, out of every possible future invention they could imagine. (Naturally, flying cars were popular, too.)

The curious thing is that Pew found people's level of interest in time travel had a lot to do with how old they are. About 11 percent of 30-to-49-year-olds said a time machine was the one futuristic device they'd want to own, but only 3 percent of people older than 65 said so.

And looking across demographics of the entire study group, people under 50 were way more into time-travel than people older than 50.

Why is that?

It's not as though time-travel is a concept tied to a certain generation. Such stories have been around for centuries. And a "major time-travel work" has come out pretty much every decade since H.G. Wells published "The Time Machine" in 1895. That's according to Kij Johnson, associate director at Kansas University's Gunn Center for the Study of Science Fiction. She also sees why the concept may become less appealing to someone as she gets older.

"What do people do when you give them time travel? They go right to the unhappiest moment of their life and they go back again and again and again trying to fix it," she said. "As an older person, there are more of those events. I'm 54. Do I really want to go back to the core terrible experiences and reengage with them, or do I feel like I've moved past them or around them?"

"Technology changes people."

James Gunn, 90, is the founding director of the Gunn Center for the Study of Science Fiction. Gunn says for the first time in his life he can now acknowledge the fact that he won't read everything he wants to read. He'd no longer take a trip to outer space if given the chance. But he would like to revisit his childhood and see his parents when they were young, maybe offer some romantic advice to his younger self.

"If I had an opportunity to use a time machine, I probably would," Gunn told me. "I'd maybe tell my younger self to be a little more sociable, less bookish."

Later, having given the question more thought, he emailed with more ideas about his itinerary through time. "My older son died of problems associated with colon cancer. I wish I could go back and make him have a colonoscopy as soon as problems began to appear. Or put a light in the hall so my wife didn't fall over our cat in the middle of the night and break her leg. Or [tell] my younger self not to go out golfing with my brother in shorts and get a bad sunburn on my legs... Nothing that would affect the course of life but would avoid pain."

But the Pew study offers another interesting layer by which to assess differences in generational attitudes because researchers also asked how people feel about real-life technology.

The older respondents who were less likely to say they wanted time machines were also much less interested in future inventions of any kind. Some 15 percent of 50- to 64-year-olds and 15 percent of those who are 65 and up said they weren't interested in any futuristic inventions. Even larger percentages of those groups (25 percent and 41 percent, respectively) said they simply didn't know what futuristic device they might want.

These older adults were as optimistic as younger people about long-term changes associated with technology, they just weren't as engaged with the specifics. In other words, Americans older than 50 are less enthusiastic about both emerging technologies and imagined ones.

"Technology changes people," Gunn said. "I find myself at this stage in my life saying I don't really need a cell phone. I don't need a tablet. I'm far more interested in simplifying existence rather than complicating it."

The interplay between science fiction and reality can be revealing. How we think about technologies that don't exist is directly connected to how we think about the devices that already do.

"If you're 70 years old, your brain is a time machine."

Maybe it's just the realism that comes with life experience. The Pew study asked respondents for all kinds of predictions about the next 50 years of science technology, and the oldest cohort tended to have more modest ideas about what might be achievable.

"Whether that's the eternal optimism of youth or the eternal realism of people who have lived a lifetime and seen the scope of change, you could definitely see a lesser expectation of what humanity can achieve among older folks," said Aaron Smith, a senior researcher at Pew.

These differing expectations—about real science and science fiction—also say something about how aging might affect the way we engage with questions about where humans are headed.

"If you're 70 years old, your brain is a time machine," said Pew's Smith. "You have seven decades of technological, social, geopolitical change. People who are going back in time would be going back to things you remember and already lived through."

Of course the lesson in most time-travel stories echoes what we learn from even seemingly minor technological shifts: The smallest changes yield important, unpredictable consequences. Usually it's not worth it, we discover. Adapting to the future is easier than screwing around with the past.

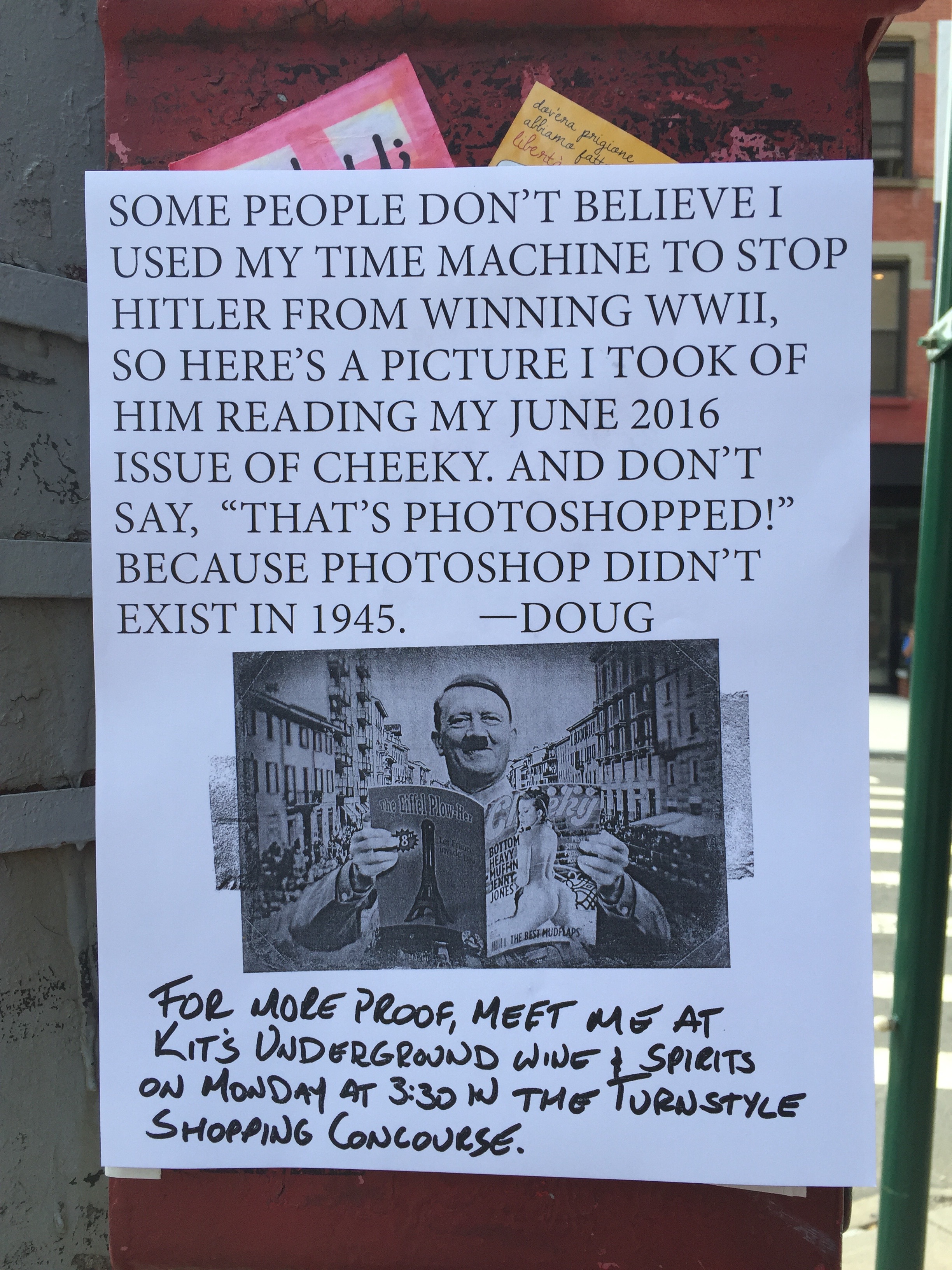

What if you COULD go back and change a dumb thing you did?

Found this at work tomorrow